The Money Tree: Part I – Where Does Money Come From?

Originally published on A Plague on Both Houses

“The process by which banks create money is so simple that the mind is repelled. When something so important is involved, a deeper mystery seems only decent.” – Economist J. K. Galbraith.

Opening this piece with the above quote is proof that I’m never going to be a successful whodunit suspense novelist. In my defence, trying to create suspense around the question of where money comes from would end up being a bit of a flop with an audience who already knows the score. So I thought: why bother?

I hope the use derived from this piece will lie not only in proving to doubters that banks really do just click a mouse to create money, but to also have a bigger discussion about why they do it, what it means for the economy, and what hope there is for change. Crucially, I am offering a money-back guarantee that this piece will decode hitherto inscrutable financial concepts in plain English intelligible to a six-year old.

Where Does Money Come From (2012 edition) was written by four reasonably high-powered financial brains, one of whom is Professor Richard Werner, the first person to propose Quantitative Easing (QE) to the Bank of Japan in 1995. Werner knows a fair bit about how the banking system works and, notwithstanding his invention of QE, seems to be on our side. I wouldn’t class the book as a fun read, but it’s very effective at drawing a line under the question of who is in control of the money supply, and how they pull the levers. In this piece I will draw on the book to discuss:

How money gets created.

How bank-created money has been used in the economy and why.

The implications for the West and some thoughts on wresting control of the system from the banksters.

To help you understand how banks create money, I’ll need to arm you with a very basic grasp of double-entry accounting. After all, money creation is essentially an accounting trick in the banks’ books. But don’t panic – it’s easy peasy lemon squeezy. When you discover how easy double-entry accounting is, you’ll wonder why accountants have to pass exams to get qualified.

Popular misconceptions

As we progress towards the mechanics of money creation, clearing up popular misconceptions may complement the overall discussion.

A popular misconception is that banks need to wait for a customer to deposit money before they can loan it out to someone else. A more sophisticated version of this is based on ‘fractional reserve banking’, which posits that banks lend out multiples of the cash and reserves held at the Bank of England (BoE). This is closer to the truth but still misleading. The ability of banks to create money is in fact very weakly linked to the reserves they hold at the central bank. At the time of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), banks held only £1.25 for every £100 issued as credit.[i]

The reality is more disturbing. First, the making of a loan by the bank creates a new deposit in the borrower’s account. Second, it is the commercial banks that determine how much reserves the BoE needs to maintain to ensure the system functions.[ii]

Another popular misconception is that the money you deposit with a bank legally belongs to you. In fact, it belongs to the bank, which takes legal ownership of the money and then records a liability to the customer. Once you’ve deposited money with the bank, you become a creditor. Your creditor status is what makes the ruse of bail-ins legal. I covered bail-ins in Part III of the BIS series under the heading “What happened in Cyprus won’t stay in Cyprus – bail-ins”. Bail-ins are a lesson in why you should not confuse legality with morality.

A widely held but false theory of banks’ role in the economy is that they act as intermediaries. This idea posits that depositors save their money and banks act as a lubricant in the system by making unutilised money (savings) available to borrowers for investment opportunities. Under this widely accepted theory, banks are neutral players performing a vital ancillary service. This is not true because if banks create and allocate money, as has been proven, they are directly involved in economic stimulus or contraction.

Where does money come from?

The UK’s money supply exists in three main forms:

Cash – bank notes and coins.

Central bank reserves – reserves held by commercial banks at the Bank of England (BoE).

Commercial bank money – bank deposits.

The first two, which the authors refer to as “central bank money” or “base money”, are now created in the UK only by the Bank of England.

Notes and coins are printed/minted under the authority of the BoE. This physical cash accounts for around 3% of the total stock of circulating money in the economy (1 and 3 above). Commercial bank money makes up the remaining 97%, as most payments for large sums are made electronically. While cash accounts for only 3% of the total money supply in circulation, it remains a key lever of privacy. However, this is not a discussion about privacy and the central planners’ aim to achieve total control through total digitalisation of the payment system.

Central bank reserves represent electronic money created by the BoE and are not available to the public. Only high-street and commercial banks that have accounts with the BoE can access these reserves, and they are used for inter-bank payment settlement and to maintain liquidity within the banking system.[iii]

Commercial bank money or bank deposits are what’s in your bank account. Not all deposits with banks derive from deposits made by the public. When banks lend money, they simultaneously create a deposit in the borrower’s account enabling them to access the borrowed funds. This is the money creation process.

The BoE’s standard definition of the ‘money supply’, known as M4, comprises cash and commercial bank money (bank deposits) (1 and 3 above).[iv] At the time of publication of Where Does Money Come From, physical cash made up 3% of the money supply and commercial bank money accounted for the remaining 97%.[v] In February 2025, the BoE said the percentages were 4% and 96% respectively. The total M4 value at January 2025 was £3.1 trillion.

So we’re going to focus on commercial bank money, which is created when commercial banks extend or create credit either through making loans or buying existing assets.

Before we discuss actual money creation mechanics, let’s debunk the multiplier model of banking as the sole explanation for new money creation.

Why the ‘multiplier model’ of banking is far from accurate

Supposing Customer A deposits £1,000 into his account with Bank A. The bank knows the customer will not spend all the money at once, and, because it is mandated by the BoE to retain a small reserve of, say, 10% of the money deposited, it lends out £900 to Customer B. Customer B now has £900 to spend, and so an original deposit of £1,000 has turned into £1,900.

When customer B spends her £900, this is received by a business that banks it with Bank B, which now has £810 to loan out to someone else.

After 204 iterations of this process, a single deposit of £1,000 will have expanded into bank deposits of £10,000. The model implies three things[vi]:

Banks cannot start lending until money has been deposited with them. It thus supports the idea that banks are intermediaries in the process of credit creation.

The central bank can closely control lending by altering the reserve ratio.

The growth in the money supply is mathematically limited.

All of these assumptions are untrue simply because banks do not wait for deposits in order to make loans. The primary criterion that banks use to make a loan is their confidence in the capacity of the borrower to repay it.[vii] Recall that at the time of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), banks held only £1.25 in reserves with the central bank for every £100 issued as credit.

The BoE Deputy Governor confirmed this in 2007 when he said:

“Subject only (but crucially) to confidence in their soundness, banks extend credit by simply increasing the borrowing customer’s current account, which can be paid away to wherever the borrower wants by the bank ‘writing a cheque on itself’. That is, banks extend credits by creating money.”

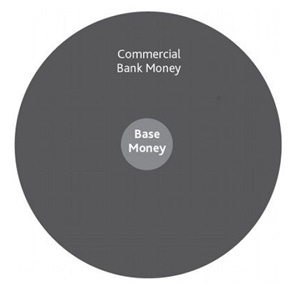

To truly understand the total money supply and its impact on the economy, we should visualise the money supply as a small core of ‘base money’, representing central bank reserves available to commercial banks for payment settlement and liquidity, surrounded by a balloon of commercial bank money resulting from credit creation. The latter is the real driver of economic activity. As we shall see when we discuss where money goes in Part II, the use to which commercial bank money is put once it’s created determines the nature of this economic activity.

This explains why the BoE’s Quantitative Easing (QE) programme during the GFC, in which hundreds of billions of new base money was pumped into the banking system, did not result in any noticeable impact on lending and economic activity. The ratio of commercial bank money to base money simply decreased. Lending came to a grinding halt at the start of the GFC, and banks did not resume lending – i.e. expanding commercial bank money – when they received more base money from QE. Banks simply used the QE money to plug the holes in their balance sheets that had arisen from bad mortgage assets that they happily sold to the BoE in exchange for base money.

When banks are confident, they create new money by creating credit. When they are fearful, they stop lending. It is the size of the commercial bank balloon that is a key determinant of the boom / bust cycle.

From the horse’s mouth

Who says commercial banks create money when they make loans? The bankers themselves say it! Here it is from the horses’ mouths[ix]:

“By far the largest role in creating broad money is played by the banking sector… When banks make loans they create additional deposits for those that have borrowed.” – Bank of England (2007)

“… changes in the money stock primarily reflect developments in bank lending as new deposits are created.” – Bank of England (2007)

“Each and every time a bank makes a loan, new bank credit is created – new deposits – brand new money.” – Graham Towers (1939), former Governor of the central bank of Canada

“The actual process of money creation takes place primarily in banks.” – Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago (1961)

“In the Eurosystem, money is primarily created through the extension of bank credit… The commercial banks can create money themselves, the so-called giro money.” – Bundesbank (2009)

So how exactly do they do it?

The mechanics of money creation

And now for the moment you’ve all been waiting for on Plague on Both Houses: sexing up double-entry bookkeeping.

The mechanics of money creation are disturbingly simple. Assume a customer, who we shall call Robert, receives a loan from Barclays for £10,000. The authors’ explanation of Barclays’ accounting for this loan requires no further simplification, so I will quote them directly:

“Upon signing, Barclays records it [the loan] as an asset on its balance sheet. Of course, double entry bookkeeping requires an equal and opposite accounting entry, and besides, Robert now wishes to get access to the money. So Barclays creates a new bank account for him, and gives it a balance of £10,000. This account is a liability of the bank to Robert, so it is recorded on the liabilities side of Barclays’ balance sheet.” [emphasis added]x]

And here is the most fiendishly complicated graphic you will ever see to illustrate the above transaction:

“Ah, but where does Barclays get the money to honour the payments Robert will make out of his newly-created deposit account when he draws down on his loan?” I hear you ask triumphantly. Well, with another double entry, Barclays will simultaneously reduce Robert’s deposit liability (the right-hand side of the diagram above, which is the money it created to make the loan), and reduce either the real cash reserves it has or its central bank reserves (base money). Recall that all banks keep accounts with the BoE which are used precisely for this purpose – inter-bank payment settlement and to maintain liquidity.

This also very neatly reinforces the authors’ assertion that it is the commercial banks that determine how much reserves the BoE needs to maintain to ensure the system functions, and not the other way around. Thus, central bank reserves maintained by commercial banks fluctuate with the ebb and flow of commercial bank lending. The question then arises as to how much must be retained by the bank in the form of its own cash and central bank reserves to meet Robert’s, and all the other borrowers’, desire to convert their loans to cash or make payments to other deposit holders. The answer is that for cash reserves, it needs to hold a small fraction in cash because the demand for cash in the economy is very low in comparison to the demand for electronic money. The ratio of central bank deposits to commercial bank deposits is also quite low (1:15 in 2010), so all in all, central bank reserves may increase by about 10% of the loan value.

Why would banks resort to the mundanity of double-entry accounting to do something as nefarious as printing money? Well, they don’t have a choice. All transactions have to be accounted for, including money-creating transactions. It’s not necessarily the case that the accounting for a transaction tells you everything you need to know about that transaction, but the accounting, assuming it reflects the real intention of the party originating the transaction, tells you what assets and liabilities have been created or extinguished.

All you need to appreciate to understand that you have not been blinded by science is that all transactions entered into by individuals or businesses always affect two aspects of your wealth. Double-entry accounting is the science behind transaction recording, and it reflects the ruthless logic of that double effect. Some illustrative examples:

When you receive your salary of, say, £2,000 at the end of the month, you have received income which increases your net worth. But you have also increased your bank balance by £2,000 to reflect your toil. So you simultaneously record an increase in income and an increase in your bank account.

You decide to sell your old banger for £500. On the one hand you have lost a car, but on the other hand you have gained some cash. So you record a reduction in the value of the assets you hold (the car is gone), and you record an increase in your bank balance.

You loan a friend £100. So, just like Barclays in the above money creation scenario, you record a loan asset of £100 to reflect the fact that your friend will (hopefully!) pay you back one day, and you record a reduction in your cash reserves. (Unlike the bank, you can’t create a deposit liability for the second leg of that transaction and then draw on central bank reserves to honour your commitment to loan your friend money. So you just have to part with your hard-earned cash!)

There is basically no transaction in the world of personal or business finance that doesn’t have this double-whammy effect. That, dear reader, is why accountants do it by double entry. They get their jollies from this simple and yet unrelentingly ruthless logic. If you grasped the above concept and examples, you are now a qualified accountant. You’re very welcome!

But more importantly, you now also know how banks shake the money tree when they create loans.

The repayment of loans creates a virtuous circle which sustains more lending. Again, the authors’ explanation of the credit cycle is elegant:

“Just as banks create new money when they make loans, this money is extinguished when customers repay their loans as the process is reversed. Consequently, banks must continually create new credit in the economy to counteract the repayment of existing credit. However, when banks are burdened by bad debts and are more risk averse, more people will repay their loans than banks are willing to create new ones and the money supply will contract, creating a downturn.”[xi] [emphasis added]

This is how banks play a key role in determining the economic cycles of boom and bust by inflating or deflating the money supply. It’s a central pillar of the Quantity Theory of Credit, which we’ll revisit in Part II, and which posits that the quantity of credit is the decisive factor in macroeconomic outcomes. Adapting Bill Clinton’s famous 1992 presidential campaign slogan to emphasise the point: it’s the money supply, stupid.

Part II discusses where our money goes once created. We’ll look at a relatively new form of money creation, Quantitative Easing, and where that money goes when it’s created. We’ll then discuss the implications for the West.

[i] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 1.2.2.

[ii] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 1.2.2.

[iii] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 2.4.

[iv] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 2.4.

[v] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 1.2.1.

[vi] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 2.6.

[vii] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 2.7.

[viii] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 2.7.

[ix] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 2.5.

[x] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 4.2.

[xi] Ryan-Collins, Greenham, Werner and Jackson, Where Does Money Come From, New Economics Foundation, London, 2012, section 4.3.2.